This project explores how public design can influence helmet use among Dutch cyclists by shifting risk perception and social norms. Instead of redesigning the helmet, I created subtle public interventions that make helmet use feel normal, relatable, and culturally accepted.

Bachelor graduation project

16 Week Individual project in collaboration with Radboud UMC & Artsen voor Veilig Fietsen

My Role

Research, concept development, prototyping, field testing, reflection

The problem

Research showed that most cyclists understand that helmets are safer, yet still choose not to wear one. This isn’t because of a lack of information, but because:

- Cycling infrastructure feels very safe

- Helmets don’t fit social norms

- Wearing one can feel uncomfortable or out of place

Design question

How can public design interventions influence perceived risk and social attitudes toward helmet use among Dutch cyclists?

Key insights

From literature, expert interviews, market analysis, and conversations with cyclists:

- Low perceived risk plays a bigger role than lack of knowledge

- Social stigma strongly influences helmet behaviour

- Most convenience issues are already addressed by existing products

- Personal stories have more impact than statistics

- Fear-based messaging risks discouraging cycling altogether

These insights led me to focus on perception and culture, rather than functionality.

Design direction

I chose to design beyond the helmet itself and focus on public interventions that:

- Exist directly in cycling environments

- Make risk feel real, but not frightening

- Shift social norms rather than forcing behaviour

- Invite reflection instead of judgement

Early concepts that relied on force, convenience, or fear were intentionally abandoned after feedback from experts and users.

Final concepts

Instead of one solution, the project resulted in two complementary public interventions, each addressing a different barrier.

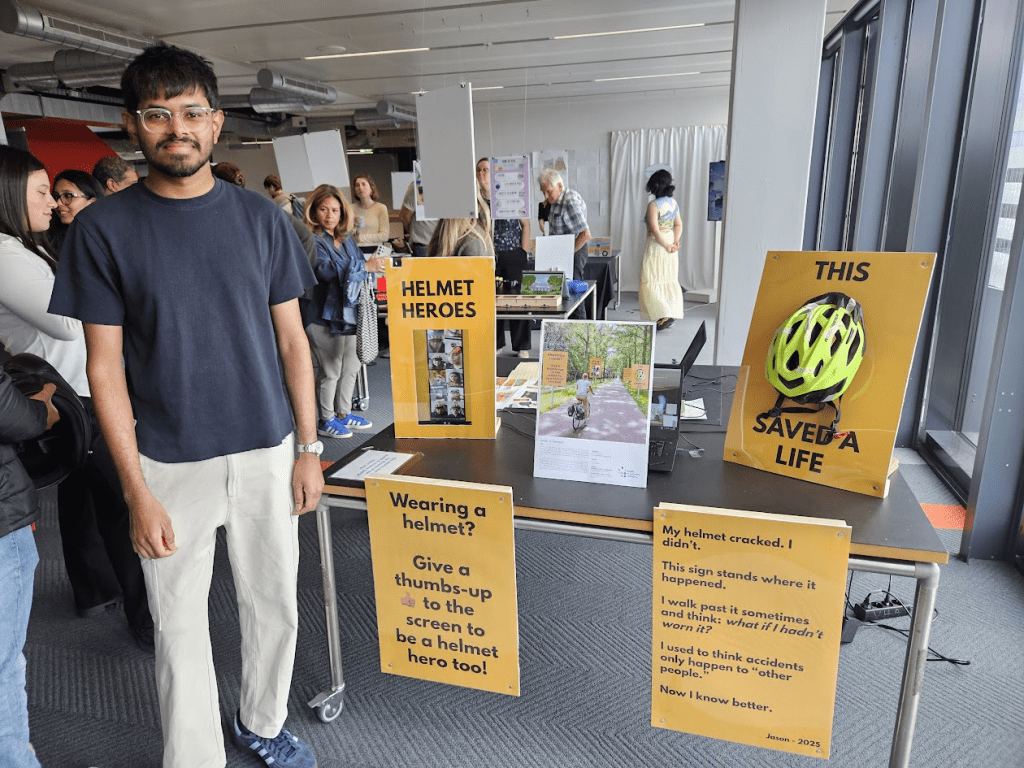

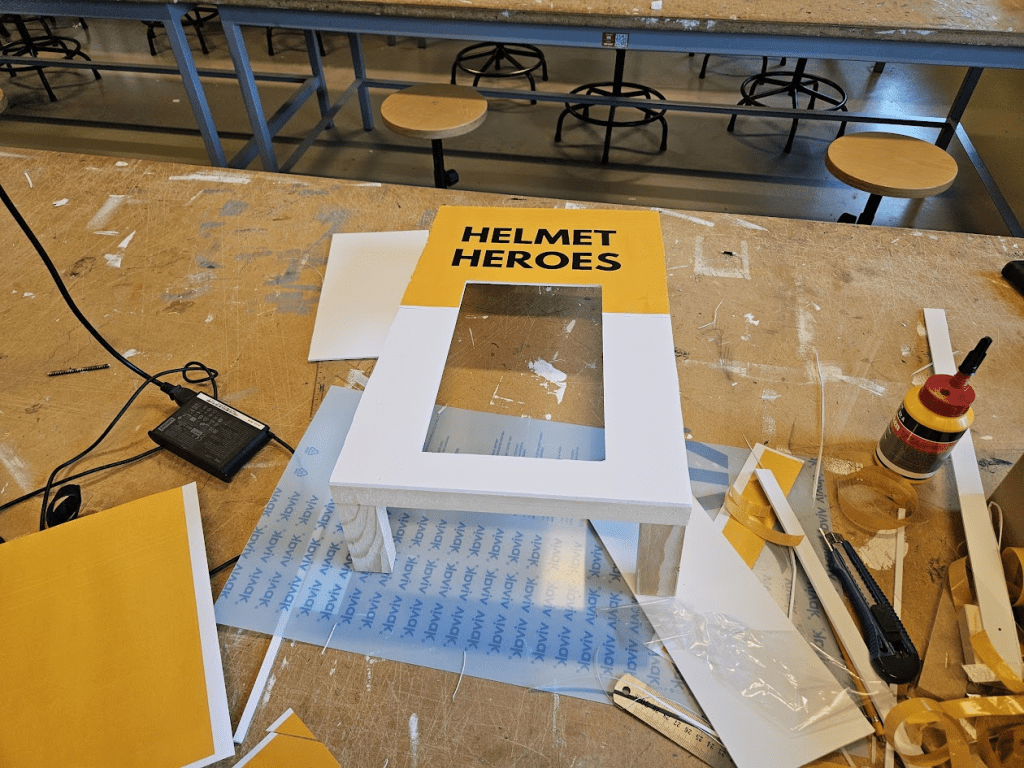

Helmet Heroes

Helmet Heroes focuses on social perception.

It is a public installation that celebrates everyday cyclists who wear helmets by making them visible in a positive way. Cyclists who choose to wear a helmet can interact with the display and become part of a growing collage of “helmet heroes”.

By showing real people rather than idealised role models, helmet use becomes normal, relatable, and socially accepted — not something strange or excessive.

The interaction is simple and playful, turning a private behaviour into something shared and celebrated.

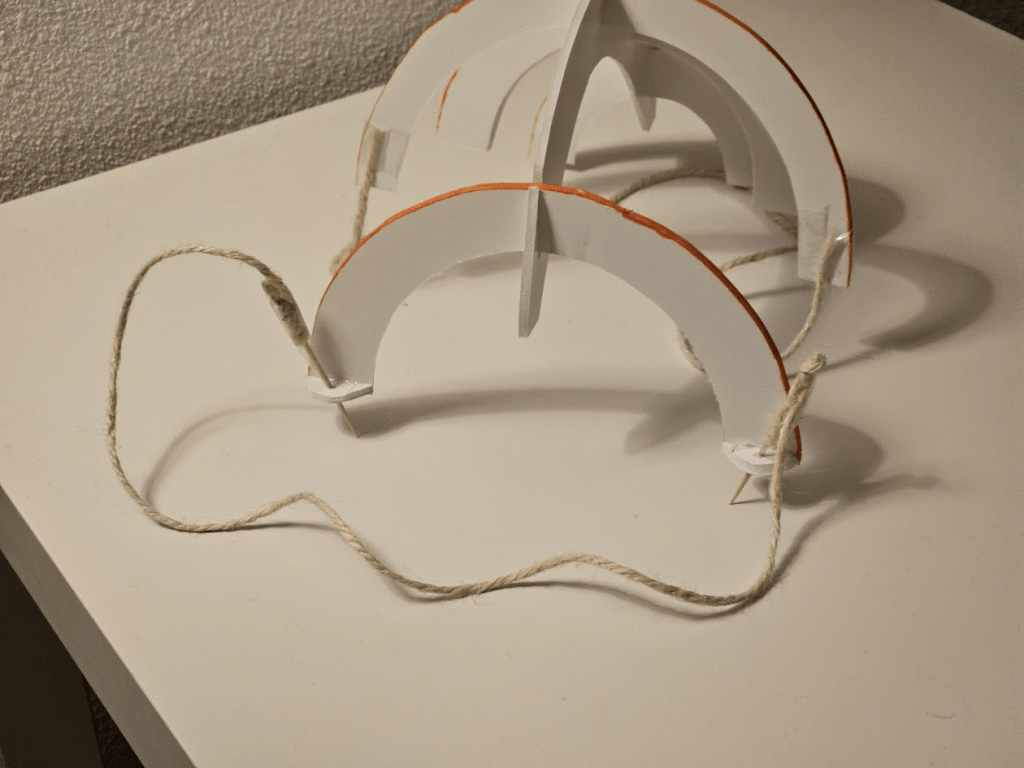

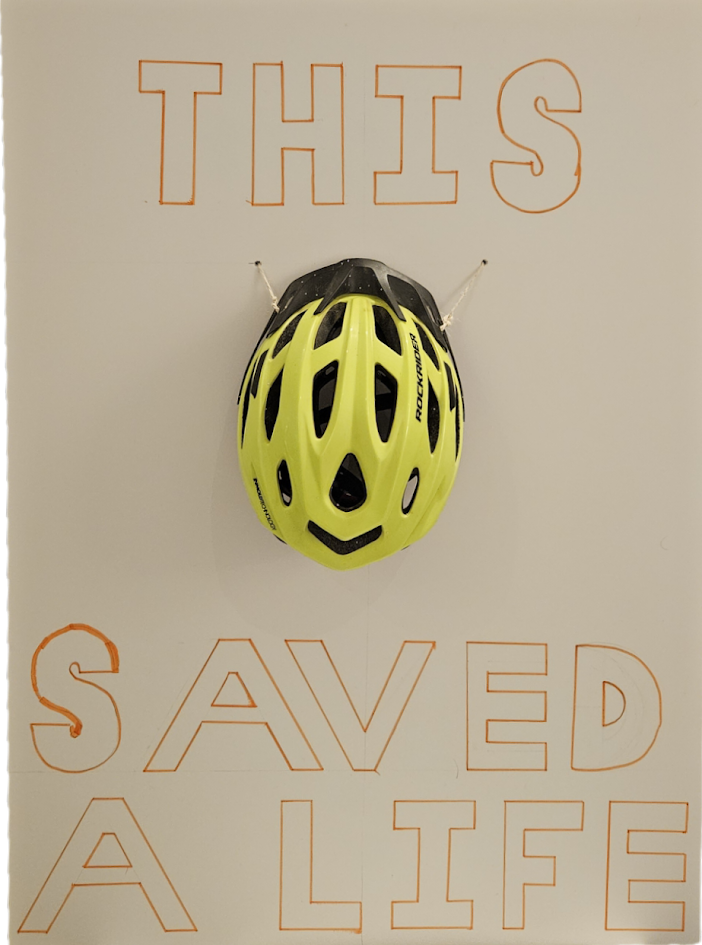

Accident Memorial sign

The Accident Memorial sign focuses on risk perception.

Placed at real accident locations, the sign displays a damaged helmet along with a short personal story about the crash. The goal is not to shock, but to make accidents feel more real and closer to home.

Inspired by memorials, the design creates a brief pause in the cycling routine. The bright yellow colour draws attention, while the story stays calm and human. Instead of fear, it encourages reflection: this happened here — and a helmet made a difference.

Prototyping & testing

Both concepts were prototyped at scale and tested in public spaces.

Field observations and short interviews showed that:

- People notice and discuss the installations with others

- The memorial sign increased perceived risk, even after only a few seconds of exposure

- Helmet Heroes felt positive and non-judgemental

- Interaction time in public space is extremely short, so clarity is essential

The tests confirmed that subtle, human-centred messaging works better than pushy or instructional approaches.

Reflection

This project shaped how I think about design for behaviour change. I learned that changing behaviour isn’t about convincing people with facts, but about creating moments that feel personal, relatable, and respectful.

Designing in public space also taught me how powerful small interventions can be. A sign, a story, or a shared image can start conversations and slowly shift norms without forcing anyone to change.

If I were to continue this project, I would explore long-term deployment and measure how repeated exposure influences attitudes over time. I would also refine both concepts for different urban contexts.

This project confirmed my interest in using design to influence culture, perception, and everyday behaviour — especially around safety and wellbeing.